Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE)

This tutorial aims to introduce the concepts behind the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE), the default hyperparameter optimization algorithm in Optuna. We will delve into key ideas in Bayesian optimization, such as surrogate models and acquisition functions, and demonstrate how TPE differs from Gaussian Processes (GP), another popular method for Bayesian optimization.

Bayesian Optimization

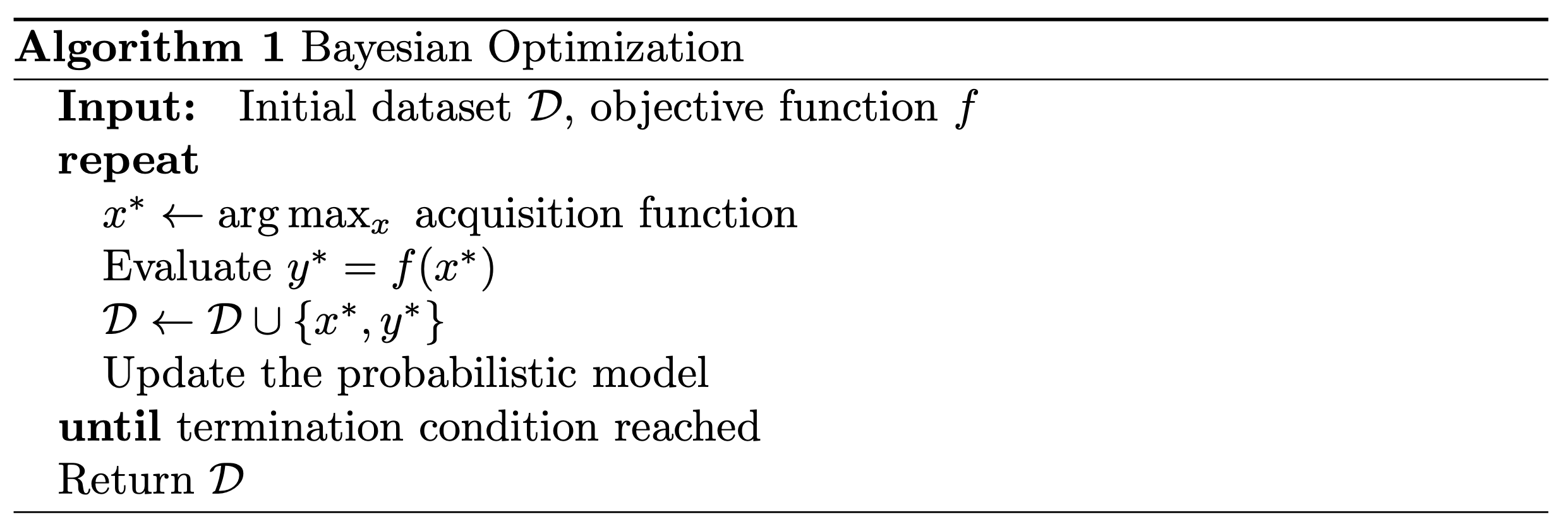

Bayesian optimization (BO) is a technique for optimizing unknown functions based on observations. It involves making sequential decisions about which new points to evaluate, aiming to improve the optimization process by focusing on areas of the search space that are likely to yield better results. It utilizes a probabilistic model estimated from the observed data to guide sequential decision-making. In this section, we will introduce the core principles of BO to provide a foundation for understanding how TPE operates within this framework - pseudo-code of the steps of BO.

Probabilistic or surrogate models

Suppose we have a set of samples ${ x\\_1, x\\_2, ..., x\\_n }$, each with corresponding stochastic observations ${ y\\_1, y\\_2, ..., y\\_n }$ in our dataset $\mathcal{D}$. The surrogate model is a probabilistic model that provides information about the underlying unknown objective function based on the available data. In other words, it helps us approximate the underlying distribution $p(y|x)$ for any $x \in \mathcal{D}$. Since $y$ is often a noisy estimate of the true function $f$, we express it as $y = f(x) + \epsilon$, where $\epsilon$ represents the noise or stochasticity in the observations.

In the literature, surrogate models can be broadly categorized into two types: parametric and non-parametric. Parametric models use a fixed number of parameters to approximate the objective function. For example, if we employ $n$ Gaussian mixture models, we need to estimate $2n$ parameters, such as the means $\mu$ and variances $\sigma^2$. In contrast, non-parametric models do not assume a specific form for the underlying function. They do not rely on a predetermined number of parameters but can flexibly increase the number of parameters as more data becomes available. This adaptability makes non-parametric models well-suited for infinite-dimensional spaces, where they effectively use a finite subset of these parameters to approximate the data we have. Instead of fitting the observed data to a pre-defined distribution, non-parametric models estimate what the underlying distribution might be based on the observed data.

Regardless of the approach, the primary objective is to approximate the relationship between $x$ and $y$. Bayes’ theorem allows us to update our beliefs of the distribution by the posterior distribution over the surrogate model parameters as new data is observed. Thus, both parametric and non-parametric models utilize the following equation: $$ p(y|x) = \frac{p(x|y)p(y)}{p(x)} = \frac{p(x|y)p(y)}{\int p(x|y)p(y)dy} $$ where $p(y)$ is the prior distribution representing our initial beliefs about $y$, $p(x|y)$ is the likelihood of observing $x$ given $y$, and $p(x)$ is the marginal probability of $x$ under all possible values of $y$. Bayesian inference enables us to refine our estimates of the relationship between $x$ and $y$ by combining prior knowledge with new observations.

Acquisition functions

Now that we have a probabilistic model to estimate the underlying objective function, we use acquisition functions to pick our next point to evaluate. According to the choice of the acquisition function, we can let pick a point be more explorative (checking less-known areas of the search space) or exploitative (focusing on areas known to have high values based on current data).

For example, one of the most widely used acquisition functions is the upper confidence bound (UCB). The typical form of the UCB is as follows: $$ f'(x) = \mu(x) + \kappa \sigma(x) $$ where $\mu(x)$ is the predicted mean and $\sigma(x)$ is the standard deviation (uncertainty) at point $x$, both estimated using the surrogate model. The parameter $\kappa$ controls the trade-off between exploration and exploitation: a high $\kappa$ encourages exploration by sampling points with high uncertainty, while a low $\kappa$ promotes exploitation by sampling points with high predicted values.

Expected Improvement

In the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) approach, the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function is used to select the next evaluation point.

Expected Improvement acquisition function has the following form: $$ EI(x) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \max (y^* - y, 0) \right] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \max (y^* - y, 0) p(y|x)dy $$ where $y^*$ is the best (minimum) value observed so far, and $p(y|x)$ is the surrogate model. EI quantifies the amount of improvement with the new point $x$ over the current best-known value of $y^*$. One way of thinking about this acquisition function is that it tries to select the point that minimizes the distance to the objective evaluated at the maximum.

This expectation can be expressed analytically in terms of the cumulative distribution function (CDF) and probability density function (PDF) of a standard normal distribution: $$ EI(x) = (y^* - \mu(x)) \Phi\left(\frac{y^* - \mu(x)}{\sigma(x)} \right) + \sigma(x) \phi\left( \frac{y^* - \mu(x)}{\sigma(x)} \right) $$ where $\Phi(\cdot)$ is the CDF and $\phi(\cdot)$ is the PDF of the standard normal distribution. The CDF here indicates the probability that the predicted function value $\mu(x)$ is less than the current best-known value $y^*$, while PDF helps calculate the expected improvement over the current best value $y^*$ across all possible values $y$. The expected improvement will be high if the difference between the best-known value and our estimate of the function $y^* - \mu(x)$ is high or the uncertainty around the point $x$ is high.

Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE)

When using Gaussian Processes (GP), another estimator widely used in BO, to model the objective function, we typically approximate the distribution of the outputs given the inputs, $p(y|x)$, directly. In contrast, the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) takes a different approach by modeling $p(x|y)$ and $p(y)$ separately. This distinction allows TPE to avoid specifying a prior over the objective function itself. Instead, it leverages the observed data and initial distributions over inputs to estimate these densities, making it more flexible in handling complex, high-dimensional search spaces.

Tree-structured Parzen Estimators (TPE) derive their name from the combination of Parzen estimators to model the probability distributions of hyperparameters and a structured, graph-like approach to represent hyperparameter configurations. In this tree-like representation, each hyperparameter is a node, and edges denote the dependencies between them. For example, the choice of the optimizer (e.g., Adam) and the learning rate can be seen as interconnected nodes. This structured representation allows TPE to focus on updating only the relevant parts of the model when new observations are made. It also facilitates establishing dependencies among random variables, making conditional sampling more efficient and enabling the algorithm to optimize the search space faster.

To estimate the $p(x|y)$ without relying on $p(y)$, TPE updates the prior distributions of the configuration parameters (e.g., uniform, log-uniform, categorical) to a parametric mixture of densities (e.g., a mixture of Gaussians). This helps estimate each of the nodes in the graph using the observation data collected, where kernel functions, like RBF, give the similarity or distance between the observation points. Using these densities, TPE approximates the surrogate model by estimating the probabilities of the observations given the performance metric (like accuracy or error rate) using that configuration.

TPE defines $p(x|y)$ using two densities: $$ p(x|y) = \begin{cases} l(x), & y < y^* \\ g(x), & y \geq y^* \end{cases} \text{, where } y = f(x^{(i)}), x \in \mathcal{D} $$ The TPE algorithm picks the value for the $y^*$ some quantile $\gamma$ away from the observed $y$ values: $p(y < y^*) = \gamma$. This allows for observations to be picked for constructing the $l(x)$, and we don’t need to have any prior of $p(y)$ to do this.

So now let’s look at how we can apply this to the Expected Improvement acquisition function. We have a cap on the range of the values we care about, in this case, $y^*$, which allows us to remove the max operator and only look at the part where $p(y|x) = l(x)$, as we only consider the $y$ that are smaller than the $y^*$.

$$ EI(x) = \int_{-\infty}^{y^*} (y^* - y) p(y|x) \, dy = \int_{-\infty}^{y^*} (y^* - y) \frac{p(x|y)p(y)}{p(x)} \, dy \\ = \frac{1}{p(x)} \int_{-\infty}^{y^*} (y^* - y) p(x|y) p(y) \, dy \\ = \frac{l(x)}{p(x)} \int_{-\infty}^{y^*} (y^* - y) p(y) \, dy \\ = \frac{l(x)}{p(x)} \int_{-\infty}^{y^*} y^* p(y) \, dy - \frac{l(x)}{p(x)} \int_{-\infty}^{y^*} y p(y) \, dy \\ = \frac{l(x) y^*}{p(x)} \int_{-\infty}^{y^*} p(y) \, dy - \frac{l(x)}{p(x)} \int_{-\infty}^{y^*} y p(y) \, dy \\ = \frac{l(x) y^* \gamma}{p(x)} - \frac{l(x)}{p(x)} \int_{-\infty}^{y^*} y p(y) \, dy \\ $$According to the above equation, to maximize the expected improvement, we would like points $x$ with a high probability under $l(x)$ and a low probability under $g(x)$. The tree-structured form of $l$ and $g$ makes it easy to draw many candidates according to $l(x)$ and evaluate them according to $g(x)/l(x)$. On each iteration, the algorithm returns the candidate $x^{*}$ with the greatest EI.

Now, let’s see how we can estimate $l(x)$ and $g(x)$ using Parzen window estimators, a statistical model for density estimation, which is also called the kernel density estimator. Given the type of the $x$ (integer, real, categorical), Parzen estimators approximate the densities differently. For real values, the formula is $$ p(x) = \frac{\sum_{x' \in D_x} w_{x'} k(x, x') + w_p k(x, x_p)}{\sum_{x' \in D} w_{x'} + w_p} $$ where $D_x \in \{D\\_l, D\\_g \}$ is a set of observed data points in either of the distributions, $w\\_{x'}$ is the weight for each observed data point (it can be set to favor the most recent data more, but they are often set uniformly), $x\\_p$ is the prior distribution (uniform, log-uniform) and $w_p$ corresponds to the weight for the prior distribution. $k(x, x')$ is the kernel function measuring similarity between $x$ and $x'$, which in TPE is usually set to a truncated Gaussian distribution $\mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma, a, b)$. In other words, TPE uses a weighted average of truncated Gaussian distributions to approximate a continuous density function of the given observations.

$$ k(x, x') = \begin{cases} \exp\left(-\frac{\|x - x'\|^2}{2 \sigma^2}\right), & \text{if } a \leq \|x - x'\| \leq b \\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $$For categorical or discrete values, a simple weighted histogram is used to estimate the density $$ p(x) = \sum_{x' \in D_x} w_{x'} \textbf{1}_c(x) + w_p, $$ where each category $c \in X$ $$ \textbf{1}_c(x) = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{ if } x = c \\ 0, & \text{ otherwise.} \end{cases} $$ In other words, it updates the histogram according to the weighted occurrences of the observed categorical values.

To account for the dependencies between the parameters, Optuna uses Multivariate TPE sampler, which models $l(x)$ and $g(x)$ directly using single multivariate Parzen window estimators.

References

Takuya Akiba, Shotaro Sano, Toshihiko Yanase, Takeru Ohta, and Masanori Koyama. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization frame- work. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining, 2019.

James Bergstra, R´emi Bardenet, Yoshua Bengio, and Bal´azs K´egl. Algorithms for hyper-parameter optimization. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2011.

P Kingma Diederik and Jimmy Ba. Adam: A method for stochastic optimiza- tion. International Conference for Learning Representations, 2015.

Shuhei Watanabe. Tree-structured parzen estimator: Understanding its algo- rithm components and their roles for better empirical performance. arxiv abs/2304.11127, 2023.